Feature Article: Greening cities and saving lives

Summer in the city – it’s the shimmering haze above softening asphalt, radiant heat off a brick wall, or the drone of air conditioners overnight. Absorption and retention of heat by hard, impervious surfaces can create urban heat islands – cities that remain significantly warmer than surrounding areas. To those vulnerable to heat stress, such as sick or elderly people, these few degrees can be critical. Already, heatwaves kill more Australians than any other natural disaster; and as our changing climate ramps up the frequency, intensity, and severity of such events, the imperative to mitigate extreme heat grows ever stronger.

Cooling our cities will require a multi-pronged approach, says Ashley Broadbent, PhD candidate with Monash University’s microclimate group. Working on Water sensitive urban design and urban microclimate (Project B3) at the CRC for Water Sensitive Cities (CRCWSC), the group advocates using water sensitive urban design (WSUD) and urban green infrastructure (street trees, parks, and green roofs and façades) to promote cooling. In fact, Ashley points out, to say that cities are islands of heat surrounded by rural coolness is an oversimplification. The microclimate group’s interest is temperature variability within cities, and ways to reduce heat exposure.

Heat health thresholds and human comfort

Another component of the project is the relationship between extreme heat and human wellbeing. A study completed in partnership with the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility demonstrated a strong correlation between maximum daily air temperatures and mortality and morbidity; it identified temperature thresholds for Australian capital cities above which heat-related hospital admissions and deaths dramatically increase.

But air temperature doesn’t tell the whole story when it comes to human thermal comfort. Just as wind chill and other factors influence our experience of cold temperatures, variables like humidity and in particular radiant heat affect our experience of high temperatures. “When it’s 30 degrees, you’re going to feel a lot hotter if you’re in the sun than in the shade,” says Ashley. “Maximising shading is a huge part of improving human thermal comfort, and where WSUD comes into that is the ability to maintain healthy vegetation.”

Quantifying the cooling potential of WSUD

Ashley has been analysing the impact of WSUD on human thermal comfort. Little empirical data currently exists on how it influences microclimate, so quantifying the cooling benefit of WSUD will provide information to guide planning and design.

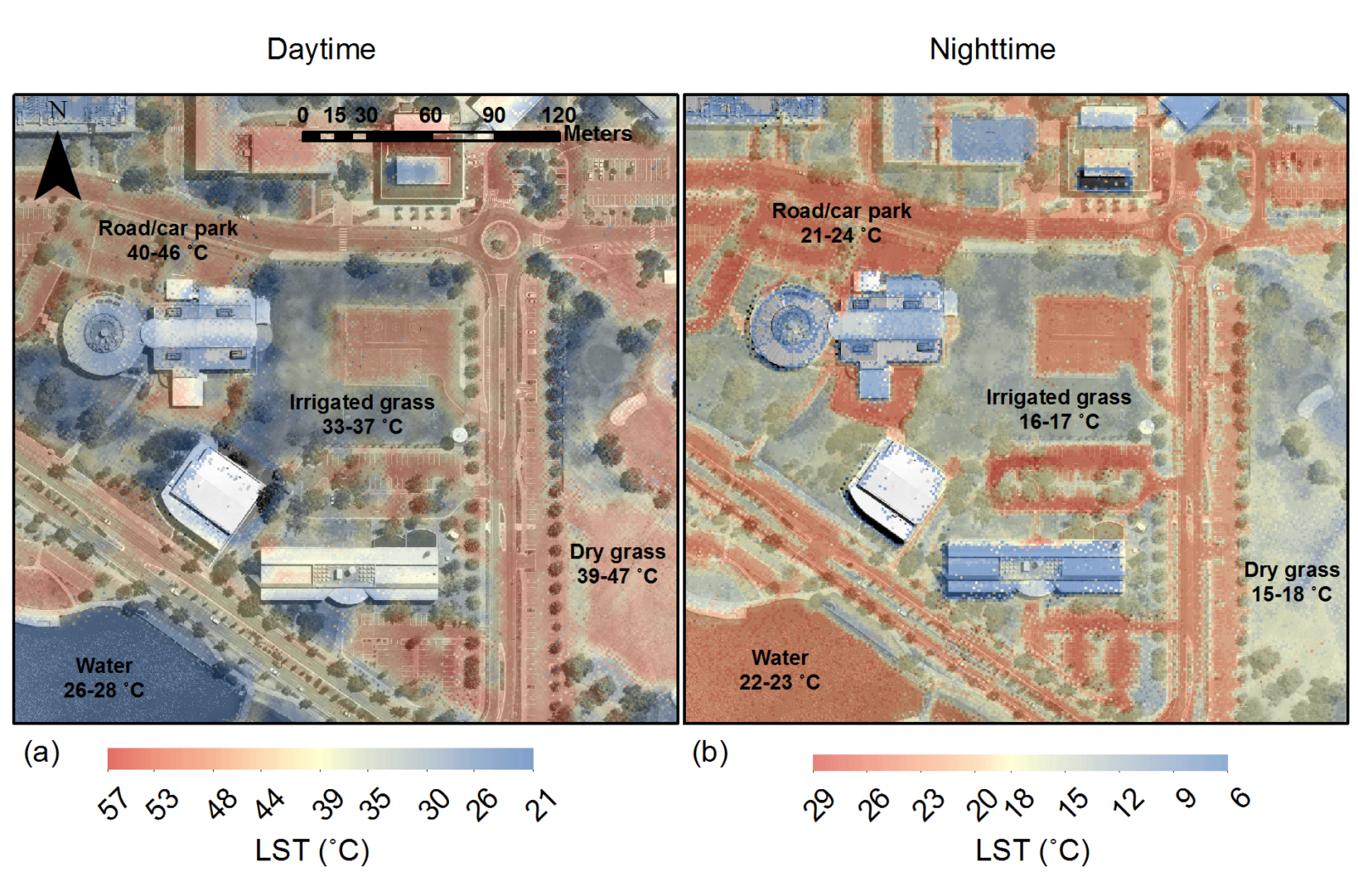

His research in Mawson Lakes – a prototype WSUD suburb in Adelaide – involved bringing together a range of observations (including in situ and remotely sensed data, and thermal imagery) and using statistical analysis to produce evidence of the cooling potential of WSUD. Although quantifying the effect on air temperature was difficult, the cooling effect on land surface temperature was dramatic.

Irrigation: the key to cooling

A clear finding was the importance of irrigation. “We do know that land surface is cooler when you integrate more water into it, and we are confident that irrigation cools the air temperature,” Ashley says. WSUD is therefore crucial: stormwater provides a sustainable water source.

Irrigation of green infrastructure to maximise its cooling potential is a fundamental recommendation of the microclimate group, based on their combined research. As well as reducing land surface temperatures and increasing evapotranspiration – both of which cool the surrounding air – irrigation is vital for tree canopy health, without which shading is less effective. The group recommends that WSUD and green infrastructure should be distributed throughout the landscape, and that trees in particular should be promoted.

Incorporating WSUD: some challenges

Providing more tree canopy is a priority for Ralf Pfleiderer, Water Sensitive Urban Design Coordinator with the City of Melbourne. Responsible for amelioration over the entire Central Business District (CBD), the council aims to plant 3,000 additional trees annually. But Ralf’s team faces competition for space – both above and below ground. “Often you’ll see streets bare of trees and you wonder why, but usually it’s because there’s a plethora of services side-by-side underground that you can’t plant over,” explains Ralf.

Nevertheless, the Council has installed hundreds of tree pits in footpaths and parking lanes. Infrastructure hidden below the surface guides stormwater through layers of sand and soil, which filter it, to water the trees. “They work in our streetscape because they don’t take up much space and trees are something people are relatively comfortable with in their streets,” says Ralf. “If we tried to create a raingarden, people look at that a bit funny.”

Indeed, people’s attitudes can be a constraint. While the council has created raingardens in development areas, some look on these unfamiliar features as a nuisance or a hazard. Ralf also explains that projects often cost more in the CBD than in the suburbs because of the need to build in protection such as bollards and tree guards.

Applying the research

“There is quite a lack of awareness of the problems associated with heat in cities,” says Ashley. “We’d like people to think about creating more thermally comfortable and thermally safer cities, through WSUD.”

It’s beginning to happen. Ashley points to the work of the microclimate group’s Dr Andrew Coutts, helping local councils to cool some of their spaces: “He’s done some great work with the City of Port Phillip: identifying ‘hot spots’, identifying areas where there’s lots of activity – where people are – and identifying where people who are vulnerable to heat are. They’ve been using that overlap to say this is an area that needs cooling. And given the characteristics of this area, what can we do to cool it.” [Planning for cooler cities: a framework to prioritise green infrastructure to mitigate high temperatures in urban landscapes, Norton et al, 2015 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169204614002503]

The microclimate group is now moving into scenario modelling. The aim is to provide information – for example, through the water sensitive cities modelling toolkit – about how much a particular environment can be cooled, under what conditions. “We see modelling as a useful way of providing that tool to policy makers and planners,” says Ashley.

It’s the next step toward creating an alternative picture of summer in the city. Think asphalt shaded by trees; a green façade covering the brick wall; and night air from a green garden wafting through open windows. Not only is it way cool; it’s lifesaving.

Nicola Dunnicliff-Wells for the Mind Your Way team