Heatwaves are silent killers — let’s keep our cities cool

Officially, it’s only the fourth day of summer. But we all know many parts of the country have been experiencing high temperatures and low rainfall for some time.

News headlines have been heralding the hot weather and its effects:

Worse than Black Saturday: Victoria braces for ‘very extreme’ heatwaves—November 2019

Melbourne matches hottest November day on record—November 2019

Many people are worried about the increased likelihood of extreme temperatures or heatwaves. That’s because heatwaves—the ‘silent killer’—are Australia’s most deadly natural phenomenon. They were responsible for approximately 55% of fatalities caused by natural hazards in Australia since 1900, which is more than any other natural hazard, and more than all other hazards combined (Coates et al., 2014). For example, the Victorian Department of Human Services reported the 2009 heatwave caused 374 excess deaths—more than double the number of fatalities caused by the subsequent Black Saturday bushfires (173 reported by the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission).

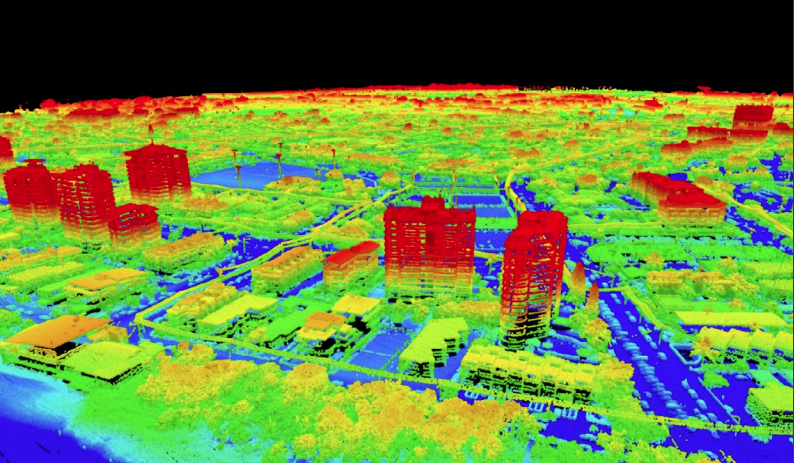

Cities can be sitting ducks for heatwaves. They’re hotter than rural areas, because of the heat stored in roads, buildings and other structures. They have less shading, less evapotranspiration and more waste heat from infrastructure and vehicles. This makes our cities vulnerable to prolonged hot weather. So, it’s important to keep temperatures in our cities below heat thresholds that cause deaths.

The hot weather and low rainfall experienced throughout much of Australia recently has again highlighted the vulnerability of our communities to dwindling water reserves. As we come into the hottest part of the year, it’s natural to focus on how to save water. And we completely agree—we must not waste water. But we can use the water available to our cities better to help keep them healthier and cooler.

Green space means cool space

When we add water, we get new ways to cool cities to combat the worst effects of heatwaves. For example, we can maximise the benefits by watering gardens and other green spaces before we have a hot day, not during that day. And we know that limited water at the catchment scale doesn’t need to impede city greening when we use water from alternative sources and realistic decentralised systems.

Several CRCWSC collaborative projects have demonstrated that more green space reduces temperatures in our cities. For example, a unique trial at Adelaide Airport conducted by SA Water showed irrigation can reduce air temperature by more than 3oC on hot days, when compared with unirrigated areas. Modelling showed increasing tree canopy cover in Dubbo could reduce land surface temperatures during heatwaves from 58ºC near hard surfaces including buildings, roofs and asphalt to 38ºC under and near tree canopies.

How we can keep our cities cool and green is the catch

This message about cooler cities is getting through, with authorities taking steps to green our cities, by planting trees, introducing roof gardens and retaining green areas when areas are developed. Planning authorities and developers are also incorporating new urban design typologies in developments, and examining ways to integrate urban and water planning:

- Adelaide Airport Irrigation Trial

- Dubbo urban heat island amelioration project

- Trees for a cool city: guidelines for optimised tree placement

- Water sensitive design typologies

- Kunshan Ring Road case study

The Millennium drought (late 1996–2009) also taught us some valuable lessons about how to use water sustainably during summer:

- Water can come from many sources, and we should use water that’s fit for purpose.

- Not all water solutions involve large infrastructure. Smaller-scale infrastructure and nature-based solutions can deliver multiple benefits.

- An informed and empowered community is vital.

So, we must use water better.

Since 2012, the CRC for Water Sensitive Cities has been researching new ways of managing urban water, and demonstrating that these new approaches can work in practice. These on-ground projects provide insights and practical solutions that can help us all use water better to keep our cities cool.

Better water use involves considering all sources

We don’t need all water to be the same. It’s time to move away from the traditional approach of a uniform quality for all purposes, and towards a system based on multiple sources of varying fit-for-purpose qualities directed at different uses.

And while water is limited at the catchment scale, cities can manufacture their own water whenever we flush the toilet and whenever it rains. Remember, storms can still occur even in drought conditions, albeit less frequently. Once treated (which is becoming easier thanks to new technologies, and smarter use of natural processes), recycled water is a viable water source. For example, households can use rainwater to water private gardens. Local governments can use stormwater, rainwater and recycled water to maintain sporting fields and other public open spaces. All of these initiatives help preserve the primary source of a city’s potable water.

Thinking laterally about water is far from business as usual, but innovative projects to create fit-for-purpose water sources are emerging:

We can better use new smaller-scale decentralised delivery systems

Traditional urban servicing is characterised by large-scale infrastructure (large dams, for instance) with long implementation lead times, which can make it difficult to respond to crises with agility.

New smaller-scale, decentralised alternative water supply systems can enhance drought resilience in cities while delivering multiple benefits across scales and sectors. They are flexible and often include nature-based solutions, such as constructed wetlands and raingardens for stormwater harvesting. They can also help keep our cities cool.

Because they are localised, they can be customised and implemented as and when needed. As a result, they can:

- facilitate out-of-sequence urban development

- defer or avoid investments for major resource development and trunk infrastructure augmentation

- service diverse urban contexts to meet local community aspirations and expected levels of service

- rapidly respond in changing situations

- adapt to new technologies as they emerge.

We have examples of smaller-scale and nature-based solutions that demonstrate these attributes:

Better informed and empowered communities are key

Building social resilience to urban heat conditions is fundamental for building city resiliency. The water sector is moving from simply providing efficient traditional ‘taps and toilets’ to fulfilling communities’ broader aspirations for health and safety. Fulfilling these broader aspirations involves ensuring all in the community are receptive to such changes. History provides many examples of innovative ideas that didn’t proceed because they did not secure community support. New water management approaches are shaped by local social, economic and environmental conditions. Their success depends on active community participation, collaborative planning and tailored designs that address people’s values.

The following examples show what’s possible when the community jumps on board:

What’s the take home message?

Saving water is a must, but using it wisely for city cooling can save lives. Water sensitive actions can help create cities and towns that are more resilient to drought and can remain cool, green and healthy when temperatures rise and dam levels fall.

Planning for extreme heatwaves is not just about the day of the event. It is also about the pre-conditions. We can’t control the weather in the short term, but we can control the way we experience it. We can act to thwart the silent killer.