INDIA—tailoring site-specific water sensitive solutions

Our work in India began in 2017, collaborating with the Australian Water Partnership (AWP) and the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), to help to enhance sustainable water management in the Indo-Pacific region.

Our work was really two projects in one; both aimed at seeing water sensitive cities adopted in India where floods, water scarcity and polluted rivers are common.

Our first project showed how to build a water sensitive city from scratch

Our first project was a rare opportunity—the chance to design a new city from the ground up, and with water sensitive design incorporated from the outset. This new city, called Amaravati, was planned to be the capital city for Andhra Pradesh. With an ambition for the city to set new benchmarks for sustainability and liveability, a water sensitive approach was well suited. The city was to be developed in stages, starting with the Government complex. The CRCWSC was engaged to provide design advice for this Government complex—initially for stormwater drainage, but expanding to include alternative water supplies and ecological waterways.

The CRCWSC worked alongside SME partners Realm Studio and Alluvium International to understand the water cycle issues facing the new city. The city planned its water supply to come from a riverine water source and to manage wastewater through a series of distributed treatment plants. Flooding would be managed via large drainage canals, which also transferred treated wastewater to the river.

The first step was to develop a city vision and water strategy for the new city, which we then translated into a more detailed strategy for the Government complex.

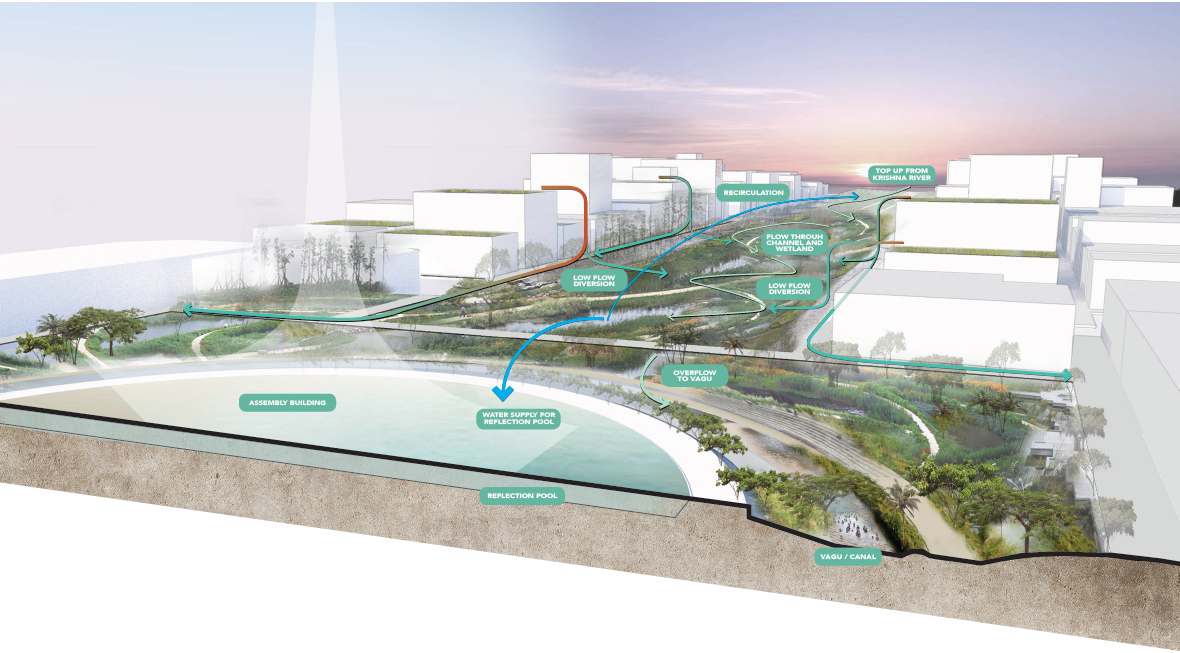

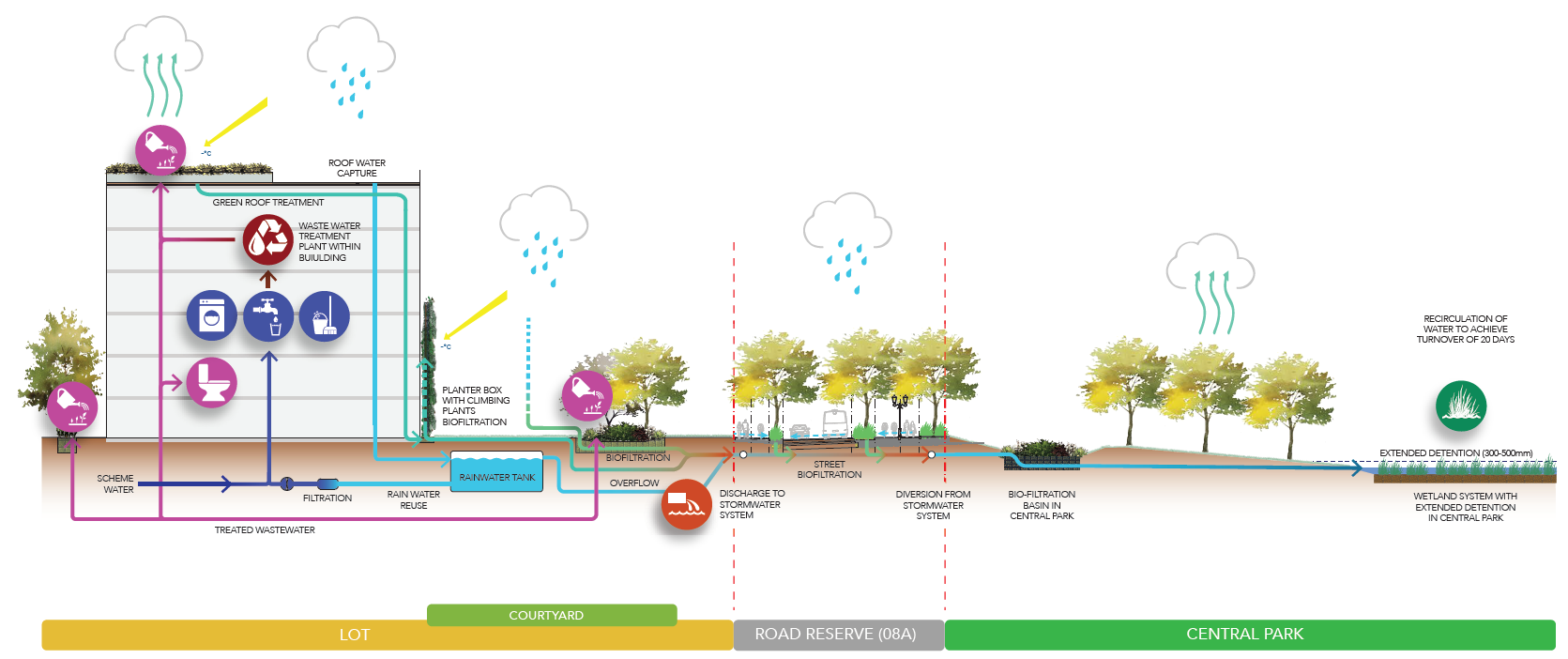

This strategy would be implemented via design typologies based on the concept of a treatment train that captured, stored, cleansed and reused water at multiple points from where it fell as rain, to where it entered the city’s major Vagu canals.

Design typologies showed how water sensitive concepts could work in practice

We then translated this concept into an urban design that focused on community level outcomes. We developed design typologies for buildings, streets and opens spaces, to show the city’s urban planners how the water sensitive approaches could be applied easily. This process involved incorporating rainwater harvesting and street tree placement into the design guidelines for the city.

Using an early version of the Scenario Tool’s Target Module, we quantified the urban heat benefits of the designs and worked closely with the architects, landscape design and urban planning teams also working on the Government complex.

Ultimately, the city’s development stalled, and has since continued with a leaner focus. The future of the water sensitive features remains unclear, yet the capacity to scope and design these new solutions remains with the Indian project partners, perhaps to influence their next projects.

Our second project showed how to incorporate water sensitive features in an existing city

Amaravati provided a platform to show what is possible with a blank canvas, representing the ‘end game’ for water sensitive city practice. It offered a benchmark to show what is possible. But to make this real for our India partners, we had to show we understood how such projects could be applied in existing Indian cities, where constraints of space and existing land uses can get in the way. We also needed to show how the proposed green infrastructure solutions work in practice. For this, our second project focused on the existing city of Vijayawada, a short distance away from the site of Amaravati.

This project involved enhancing stormwater management, urban biodiversity and green space in three canals in the city of Vijayawada, also in Andhra Pradesh. Here, we provided technical support and conceptual designs to move the city towards sustainable urban water management, and to demonstrate innovative retrofits of nature-based solutions for water management into existing urban water infrastructure.

We used designs for three canal sites (known as Ryves Canal, Eluru Canal, and Bandar Canal) to demonstrate how to create greater ecological functions in this highly urbanised city and lift the city’s urban liveability and sustainability.

The canals currently supply drinking water to downstream villages as well as irrigation water, but present several challenges:

- near constant flow of greywater, with blackwater cross-connections at all outfalls

- low water levels during baseflow, creating poor amenity and high odour

- very large litter loads, especially at outfalls and ‘snagged’ in the canals under baseflow

- open street drains vulnerable to illicit discharge of oils, fats and detergents

- poor public connection with canals and recognition of the value of linear green space.

Before we could suggest solutions to address these problems, we had to better understand:

- Who uses the canals and how? How do these groups value the canals?

- What value do the canals provide to the broader community? How does broader community value water and waterways more generally?

- What are the existing governance arrangements, and what are the relationships between these stakeholders?

- What leverage points can help move from current practice to better practice?

We engaged government and communities

Part of our process was ensuring the work attracts a critical mass of government and community engagement, to raise awareness of the multiple challenges and corresponding solutions related to urban water management. To that end, we:

- worked alongside the local project partners to conduct detailed onsite assessment and diagnostics, and reviewed existing capital works plans with local practitioners

- facilitated co-design workshops with local practitioners from the state and local government departments with interest in the management and operation of the canals to develop potential water sensitive solutions

- developed a conceptual strategy for a selected reach of one of the canals, with concept design of up to four water sensitive elements to be integrated into existing tributaries (drains) and/or canal corridor

- engaged the Principal Secretaries of Government Departments and Commissioner of the Council to ensure political support for the project.

The proposed solution to improve Vijaywada’s canals reflected local conditions

The problems experienced by people living near Vijaywada’s canals and those downstream precluded off-the-shelf solutions. Rather, the situation required a tailored solution that incorporated local knowledge and reflected the local context. Understanding the true value of the water, which is used as the primary drinking supply of numerous downstream communities, meant pollution control was vital. To improve the catchment of the drainage system, the design incorporated novel green infrastructure into tight streets. In addition, the treatment design catered for blackwater as well as stormwater entering the existing drainage system. The design also maintained hydraulic flow rates in an irrigation canal, to accommodate the needs of different government stakeholders.

The resulting water sensitive concept design creates three diverging green spines (canals) through the city that provide multiple benefits:

- enhancing urban biodiversity and habitat

- activating the canal edges and linking them to streetscapes and public spaces

- connecting more people with waterways for recreation, such as fishing

- improving aesthetics in highly visible waterways

- improving water quality for downstream villages

- reducing public complaints and politicising of issues

- improving water management as a catalyst for catchment-wide social and behavioural change.

We hope our work will have far-reaching implications and make Vijayawada a case study for other Indian cities. We also hope this work will stimulate future urban water management opportunities for Australian businesses in India and build capability among local partners.