Mind the policy gap

It is an exciting time for water sensitivity. Local councils, government agencies, developers, and communities across the country are moving rapidly toward a deeper understanding of the value and significance of creating water sensitive cities, and how implementing water sensitive urban design (WSUD) principles can contribute.

It is an exciting time for water sensitivity. Local councils, government agencies, developers, and communities across the country are moving rapidly toward a deeper understanding of the value and significance of creating water sensitive cities, and how implementing water sensitive urban design (WSUD) principles can contribute.

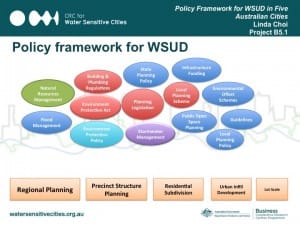

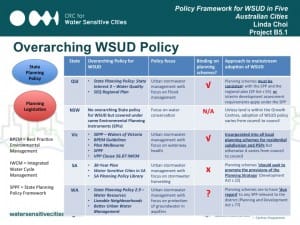

While the understanding and impetus to pursue WSUD-focused developments continues to grow, it is important to keep sight of the broader state-planning and policy frameworks within which decision makers must act. Barnaby McIlrath is the Project Leader for the CRCWSC’s Statutory planning for water sensitive urban design (Project B5.1), which recently completed a thorough literature review of the state government-related planning frameworks for WSUD in Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Perth. The review will

be published soon.

“We presented the findings from the literature review at the recent CRCWSC conference in Brisbane,” says Linda Choi, Senior Researcher on B5.1. “It was really well received, confirming that there has been a research gap in this area. Many were keen to get their hands on the literature review because they saw it as a useful resource for knowing how other states implement WSUD, and go about promoting such policy. There have been some studies done by various institutes and consultants in the past but not to the same extent as our review.”

Fragmented policy

The review reveals some potential stumbling blocks to the efficient progress of WSUD. The general concern is that there is great variability in policy between states. While such diversity isn’t always a bad thing, Barnaby says developers and planners prefer consistency so they know “where the goal posts are”. Some states, such as Victoria, have provided a clear performance-based policy driver that helps give a more consistent approach and supports the mainstreaming of integrated water management and WSUD. By contrast other states have allowed a less consistent, discretionary approach to sustainable water management that varies significantly from council to council.

“Even in Victoria there are policy gaps,” says Urmi Buragohain, a Strategic Planner from Kingston City Council. “For example, Clause 56 of the Victoria Planning Provisions requires new residential subdivisions to demonstrate compliance with best practice stormwater treatment objectives and flow management, as outlined in the Urban stormwater best practice environmental management guidelines (BPEMG) under the State Environment Protection Policy (Waters of Victoria). However, this clause applies only to residential subdivisions, and not to any other types of development. This is a particularly big issue for Kingston as we have a strong mix of multi-residential, mixed-use, industrial, and commercial developments as well.” Kingston’s situation is reflective of established urban areas that do not have large growth corridors.

“Even in Victoria there are policy gaps,” says Urmi Buragohain, a Strategic Planner from Kingston City Council. “For example, Clause 56 of the Victoria Planning Provisions requires new residential subdivisions to demonstrate compliance with best practice stormwater treatment objectives and flow management, as outlined in the Urban stormwater best practice environmental management guidelines (BPEMG) under the State Environment Protection Policy (Waters of Victoria). However, this clause applies only to residential subdivisions, and not to any other types of development. This is a particularly big issue for Kingston as we have a strong mix of multi-residential, mixed-use, industrial, and commercial developments as well.” Kingston’s situation is reflective of established urban areas that do not have large growth corridors.

While Victoria’s clause 56 has underpinned the growth of WSUD in that state, the policy framework remains fragmented. Moreover, in many states the policy implementation is left largely to the discretion of local councils, which leads to further inconsistency in approaches. This potential for inconsistency extends to governance arrangements as well: for example, who is responsible for maintaining raingardens once they are installed?

“Quite often roles and responsibilities fail to be clearly allocated between water authorities, local councils, government agencies, and property owners, to make clear who’s going to deal with, say, floodplain management or stormwater management,” says Linda. “Alternatively, the objectives of one local WSUD policy often conflict with another because they haven’t been coordinated properly. Urban planning has traditionally evolved around local council boundaries, as opposed to catchment boundaries. Frequently, councils downstream of a catchment are dealing with problems created upstream by other councils.” It’s much harder for councils to collaborate effectively without a state-wide policy or a supporting framework in place.

Directions for reform

The next step in Project B5.1 is to investigate significant reforms that can consolidate, harmonise, and simplify these fragmented national, state, and local government policy frameworks, in the interests of promoting best practice. While careful analysis still needs to be done, Barnaby and Linda suggest some possible directions for effective reform. To start with, we may need to provide a consistent and universally accepted definition of WSUD that is applicable at the national, state, and local level. This would “help to define the scope for what ‘best practice’ for urban water management means”.

With consistent definitions in place, it becomes easier to develop mandatory performance standards or requirements, providing legal obligations for decision makers to give them effect. Currently, although states identify WSUD as an important policy issue, there are generally no mandatory standards that developers have to meet (except in Victoria). In most states the policy requirement depends on whether and how well the policy objective has been implemented at the local level.

Another valuable reform focuses on the need for continuous evolution of WSUD policy – a necessity when such policy is based on cutting-edge science and technology. “Planning policy needs an adaptive framework to make it easier to update and respond to developments in technology and social expectations,” explains Linda. “It shouldn’t sit unchanged for years.”

Relatedly, updating practice with current technology can resolve another issue identified in the literature review: there are too many WSUD policy guides in some states, and too few in others. Planners and engineers need a “one-stop shop” approach to WSUD. At present, a lot of guidance is outdated, or poorly integrated, or lacks support from an overarching statutory or policy framework. Older guidance can be hard to locate, so it makes sense to consider how policies and implementation guidance can be more efficiently integrated to achieve simpler decision making, and to converge on mainstream best practice.

It is not always easy for state and local governments to access clear guidance on WSUD policy; but as Linda points out, “there is no theoretical reason why we couldn’t provide an electronically accessible, consolidated, and integrated national WSUD policy manual for educating WSUD stakeholders in how to develop good policy.”

Support for reform

Local councils are very keen on these kinds of reform. “Better frameworks”, says Linda, “mean they don’t need to spend as much time, resources, and money developing their own local policies and implementing them.”

Local councils are very keen on these kinds of reform. “Better frameworks”, says Linda, “mean they don’t need to spend as much time, resources, and money developing their own local policies and implementing them.”

Urmi confirms the importance of filling in these policy gaps. “While waiting for the state government to update the overarching policy, councils must develop their own policies,” she explains. “The development sector is becoming increasingly vocal about how stringent the current requirements are, particularly for industrial and commercial developments.” To support these industry needs, Kingston is investigating a more flexible local policy which makes use of WSUD offsets.

“Yet for projects like this, councils can’t really operate on their own,” adds Urmi. “They need the support and backing of the organisations and agencies that are involved in the water sector. Melbourne Water has its own offset scheme which works very well in growth areas, but how do these offsets operate in inner areas – like Kingston – where there is more high-density development?” Uncertain and inconsistent policy frustrates industry aims to achieve market advantages through better use of water in the design process, which in turn hinders the nation’s overall progress toward WSUD.

“Our research indicates areas where industry has been supportive of best practice approaches,” says Barnaby. “However, industry consistently expresses concern about variations between councils, or development of policies that do not apply at the state level.”

Local governments across the country have played an important and challenging role in developing policy to support WSUD in its early stages. But as project B5.1 has identified, there is now a clearly emerging need for a more unified approach, supported by policy development and reform at the national or state level. The next step in the project will be to confirm the viability of specific solutions to these policy gaps, formulating and assessing reform options in consultation with CRCWSC industry partners and stakeholders. In response to their work so far, Linda has already been invited to speak at Water Sensitive SA’s Pathways to Water Sensitive Communities Through Planning seminar and workshop to help steer their reforms, as well as the 2016 Institute of Public Works Engineering Australia Conference in Perth.

Sam Green for the Mind Your Way team.