Understanding the hydrology of the Swan Coastal Plain

Perth is Australia’s fastest growing capital city. Increasingly, urban development is occurring on the drained wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain; but seasonal inundation is a real issue, and in parts groundwater lies within two metres of the surface. In fact, because of reduced rainfall and hotter, drier summers resulting from climate change, groundwater remains a key water source. Protecting availability and quality of water is therefore crucial. However, existing attempts to manage these issues – through water sensitive urban design (WSUD), for example – have highlighted fundamental differences between this region and the cities of Australia’s east coast where many WSUD tools have been locally designed and implemented.

“Gutless grey sand” and high groundwater

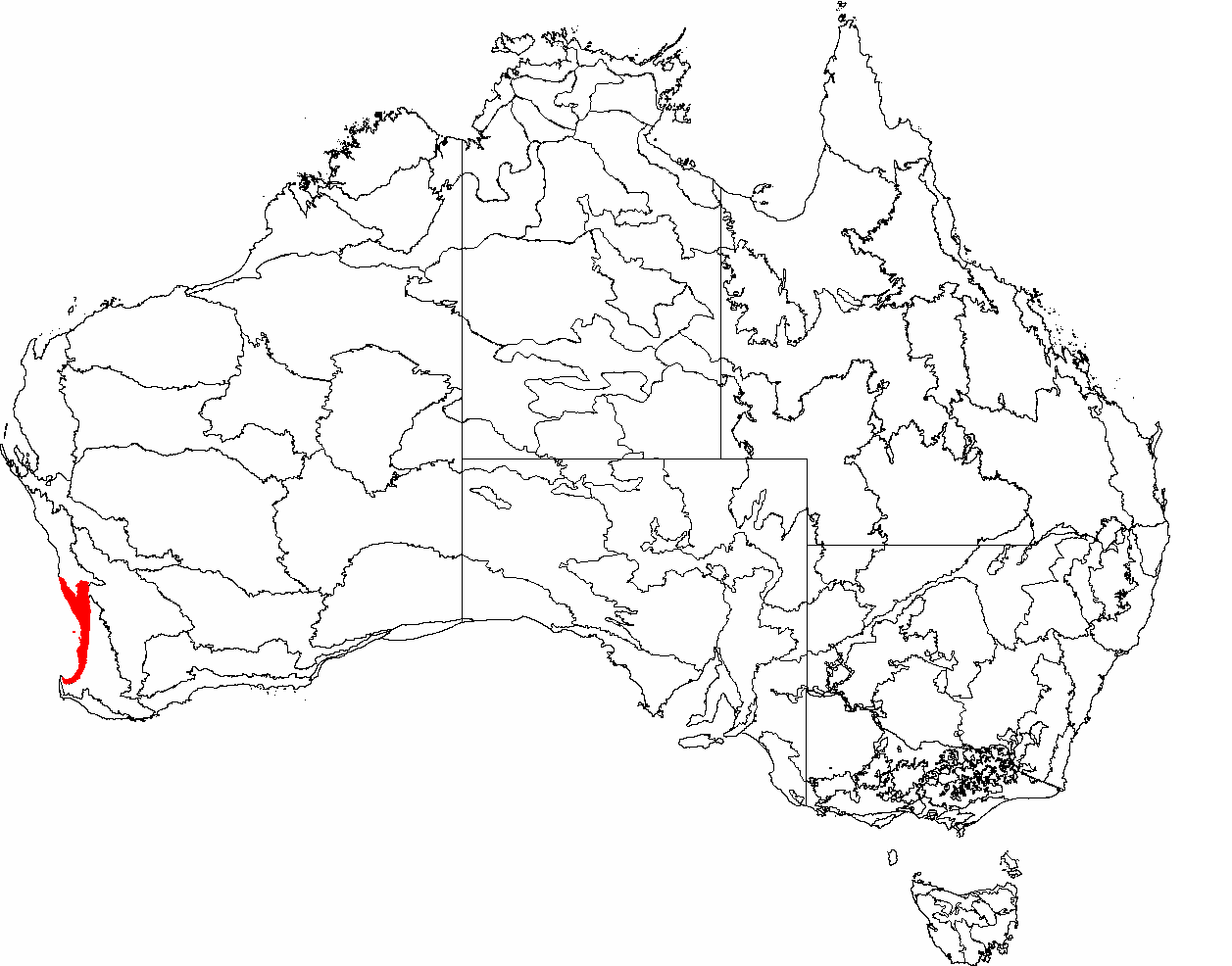

The characteristics of the Swan Coastal Plain – the narrow coastal strip between the ocean and the Darling Range, stretching 650 km from Geraldton to Busselton in the south of Western Australia – pose a particular challenge for urban development, which in turn has altered the hydrology by introducing impervious surfaces, withdrawing water, and changing drainage networks. The issue of excess nutrients contaminating waterways is compounded by the interaction between surface water and groundwater. The dominant soil type – described by farmers as “gutless grey sand” – is highly permeable, with little capacity for retaining nutrients. Unlike in many eastern-state cities, surface runoff is minimal; instead stormwater rapidly infiltrates the soil and percolates through (taking nutrients with it) to recharge the superficial aquifers, which in turn flow into rivers, lakes, and wetlands. Too much phosphorus and nitrogen, in particular, can lead to excessive algal growth, which depletes oxygen. This is expensive to fix, and causes problems such as bad odours and fish kills.

Carolyn Oldham, Winthrop Professor at The University of Western Australia, and a researcher with the CRC for Water Sensitive Cities (CRCWSC), leads Sub-project B2.4 (Hydrology and nutrient transport processes in groundwater/surface water systems). Carolyn investigates those urban and peri-urban areas of the Swan Coastal Plain that have high groundwater. She and her team strive to advance our understanding of the transport of water and nutrients from the surface through to the receiving waters (including groundwater), and the nutrient cycling that occurs along the way.

Improving our understanding to tackle issues intelligently

The many stakeholders with whom Carolyn and her team are involved – including the Western Australian Department of Water, a CRCWSC Industry Participant – stand to benefit in various ways from a better grasp of the hydrology in these areas. Understanding how high groundwater might compromise the effectiveness of WSUD and the application of water sensitive city principles is a priority for councils and developers. “We want to provide some tools that will allow designers to assess which WSUD elements should be deployed to help reduce nutrient inputs to the river,” says Carolyn. “At the moment it’s unclear what the best treatment approaches are to manage the groundwater nutrients, because we don’t understand how they are moving through the urban environment.”

A key part of Sub-project B2.4 is understanding the water and nutrient movement through a given system by completing mass balances. Like a cash flow analysis, a mass balance quantifies all the water inputs and outputs of a system so that they equalise. Groundwater is more elusive than surface water; but it’s important to quantify both because the nutrient signatures may be quite different. “We want to do a water mass balance and then a nutrient mass balance so we can be very clear about, for example, what contribution groundwater makes to the total nutrients going into a receiving water body,” says Carolyn. “We can then spend resources in the right area – otherwise we might, for instance, spend money treating surface water when groundwater is the main issue.”

A direct application

Joel Hall, a senior environmental modeller with the Department of Water, hopes that results from Sub-project B2.4 will help refine a tool he is developing to assess the amount of nutrient coming off new urban developments. Called Urban Nutrient Decision Outcomes (UNDO), the modelling tool is designed specifically for the Swan Coastal Plain’s sandy environment. It will enable developers and government agencies to calculate nutrient runoff in new developments, and assess proposed developments against appropriate targets to ensure that acceptable levels will be achieved.

“We created UNDO in response to a desperate need from the development industry,” says Joel. “Without an assessment tool it’s very difficult to ascertain whether developers are doing enough to minimise the impact of nutrients from new developments on adjacent water bodies. The industry wants this tool so they can streamline approvals with less argument, and minimise environmental harm.”

Joel believes the CRCWSC research can help make UNDO a more powerful tool. “We need to have a better handle on nutrient dynamics – exactly what is going on between water hitting the ground and it entering the receiving environment. That’s the big research gap that we hope the CRC project will help to answer,” he says. “What I see out of this in the future is the tool, the research, and the science really guiding the way that we do development and coming up with some really good planning outcomes.”

What industry wants

The University of Western Australia’s Pro Vice-Chancellor (Research), Winthrop Professor Peter Davies, is similarly passionate about the translation of research. “One of the key outputs of the CRCWSC so far has been some really strong links between researchers and [land and water] managers,” he says. Both he and Carolyn Oldham have engaged stakeholders right from the start – so industry partners have helped devise their research. According to Peter, this has been quite a change from how research is typically done. “We’re talking about a ‘management pull’ rather than a ‘research push’,” he explains: “Finding out what they actually want.”

And what managers want, says Peter, is tools – simple technical guidelines for improving, say, a wetland or a river system. “We might say ‘under these circumstances, the most effective treatment would be, for example, to revegetate the north bank of the river’.” The challenge is not to overcomplicate things: “We want to provide some simple levers they can pull. That doesn’t mean that the science is simple, but that good science underpins the tools.”

From theoretical to practical

Sub-project B2.2 aims to take a conceptual understanding of how we think water bodies work, then look at what management interventions could be made, put forward predictions about the outcome of those interventions, and develop some demonstration sites. Initial conceptual models, completed in December, have integrated existing knowledge. “They’ve got everyone on the same page, almost like a literature review, but in conceptual form,” explains Peter. “Now we can make them more interactive by adding some levers – for example, if we allocate more water, or if we replant vegetation around a wetland, here’s what we think might happen. That becomes a management tool.”

For Peter, the thought that we can actually get water in urban settings to have multiple functions is particularly exciting. “Waterways are often constructed as drains: straight lines, designed to get water off the land as quickly as they can,” he says. “From the research we’ve done already we can say that, with a little bit of work, that drain can become a river. It can start to meander; when it meanders it creates habitat, and once you have a habitat the biodiversity comes back. With clever design water can do a number of things.”

Innovation and tradition – pathways to success

Meanwhile, Peter Davies explores ways to communicate research outcomes effectively to different audiences. Recently, instead of writing papers, his team has produced DVDs for people working on water bodies. “People tend not to read much anymore,” he says, “but they will look at YouTube or a DVD to see what we’ve found.” The challenge for academics is that university reward structures don’t support this. As PVC (Research), Peter is working on the issue. “One of our main drivers now is to ‘socialise the research’: we need to find ways to get knowledge out into the community.”

Carolyn Oldham hopes that a legacy of the CRCWSC will be to rebuild expertise around groundwater–surface water systems. “There’s a real sense in Western Australia within the university system that we’ve lost the critical mass of understanding of these systems, which are key for Western Australia. I hope that nine years of the CRCWSC will re-establish that for both research and teaching; we need our graduates to go out understanding the systems where they’re working.”

As the Perth experience has demonstrated, a cookie-cutter approach to developing water sensitive cities is not enough. Understanding the hydrology of the Swan Coastal Plain will be a crucial step along the way to improving water outcomes in the region.

Nicola Dunnicliff-Wells for the Mind Your Way team