Developing and delivering the future water professional

Modern day professionals across almost every sector face numerous challenges in staying up to date with rapid and diverse technological advances. The development of new methods and technologies has shifted the focus of many employers from requiring deep experience in a particular field, to preferring prospective adaptable employees that possess a range of transferable skills, as highlighted by a recent series of reports by the Foundation for Young Australians. This change is also occurring with the water sector and several groups, including CRC for Water Sensitive Cities (CRCWSC) researchers, have been working to uncover exactly what the water professional of the future looks like. This work is vital not only to maintaining current infrastructure, but to moving into the future and improving services amid a changing climate, and in growing cities.

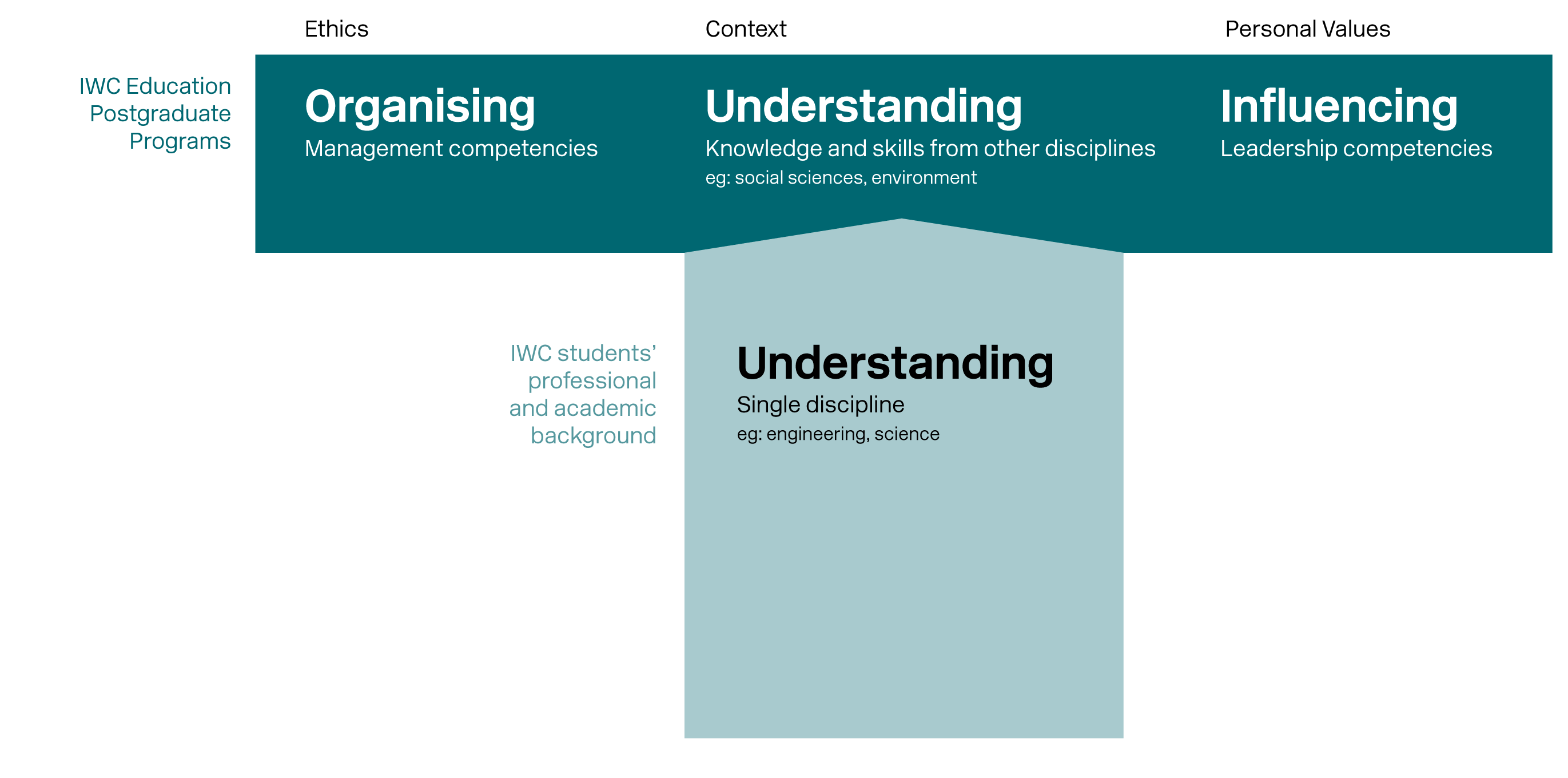

Work conducted by CRCWSC researchers as part of Project D4.1 Strengthening educational programs to foster water sensitive cities leaders, along with a new research project by the Water Services Association of Australia (WSAA), are central to discovering what skills are most valuable to the industry, and what this means for education and training programs. The International WaterCentre in collaboration with the CRCWSC has identified the T-shaped water professional as a model that describes this change. The “T-shaped” concept addresses the need for professionals who have a grounding in specific and specialised fields as well as broad transferable skills in leadership, innovation and communication.

Challenges facing the water sector

Moving into the future, the water sector faces numerous challenges in maintaining a high level of service. While some of these are similar to other industries – for example, refocusing on developing multi-skilled professionals – many are unique to the water sector. Across Australia, there is a growing concern about the water sector’s aging infrastructure base. The industry is faced not only with the question of how to manage these assets, but also with financial pressures that, as described by Jill Fagan from the WSAA, are “pushing the water sector to develop new and innovative ways to better utilise our current infrastructure.” While the water sector is embracing this new era of innovation, there are new challenges in training the workforce to implement and improve the new methods, as well as in understanding, collecting, and making use of the vast amounts of data that can now be gathered.

Another major challenge facing the water sector is the fragmentation of control over different aspects of the water cycle. With utility companies and multiple levels of government all involved it can be difficult to determine who is ultimately responsible for certain aspects of the water cycle. Brian McIntosh from the International WaterCentre says, “this results in a strong need to coordinate and collaborate in ways that are not yet established.” In particular, water professionals will need to become more articulate when conveying to specialists from different departments of the merit of future projects that help to foster this environment of collaboration.

Creating the future water professional

Uncovering the exact skills required by an industry as diverse as the water sector can be difficult, but what has become apparent is the need for individuals to work across multiple departments – something that calls for adaptability and effective communication skills. Jill Fagan says, “in the past we would have relied on experts with years of experience; we still need experts but we also need people to be more adaptive and work across a wider range of tasks.” This sentiment is mirrored by Brian McIntosh, who points out that “water professionals now need to work more effectively with each other and be able to influence and drive processes of change.”

Yet the question remains: how does the sector educate and train these more adaptive T-shaped professionals? Almost every University around the world offers a Masters of Business Administration (MBA) that helps to develop the transferable skills required to effectively run and manage any business venture, and provides a fantastic template for how water industry could work to develop more adaptive water professionals. This type of Masters-based approach has been developed by the International WaterCentre with the help of CRCWSC researchers. Such a program instils a combination of cognitive and attitudinal changes that may not be possible with shorter, on-the-job training courses. The exact makeup of this and future Masters degrees will vary depending on the latest research, like that conducted by the CRCWSC. While the skills and training methods preferred may vary depending on the specific position within the water industry, the need to focus more on broadening the skill set of water professionals – regardless of the individual’s specialisation – remains a constant. As Brian McIntosh states, “it is not just about the ‘know-what’ or the ‘know-why’, but it is about the ‘know-how’: it is about the broader skills.”

Nick Proellocks for the Mind Your Way team

Further reading

McIntosh, B.S. and Taylor, A. (2013) Developing T-Shaped Water Professionals: Building Capacity in Collaboration, Learning and Leadership to Drive Innovation. Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education.

Technical/Milestone Report: Water Sensitive Cities skills and knowledge needs.

Technical/Milestone Report: Delivering water sensitive city professional learning – Understanding the learning needs and preferences of the Australian urban water sector.

The Water Services Association of Australia: National Urban Water Research Strategy.