Getting the public onside can boost raingarden acceptance

To many local residents living near a raingarden, understanding the reasons for its construction or design style can be just as important as whether it adds value – aesthetic as well as economic – to their street.

CRC for Water Sensitive Cities researchers, including Dr Meredith Dobbie from the School of Social Sciences at Monash University, have taken up the cause of discovering why some raingardens are more appealing than others, and their impact on suburban streetscapes.

Meredith’s research has informed a new publication, Designing raingardens for community acceptance, for Cities as Water Supply Catchments – Society and Institutions (Project A4.1).

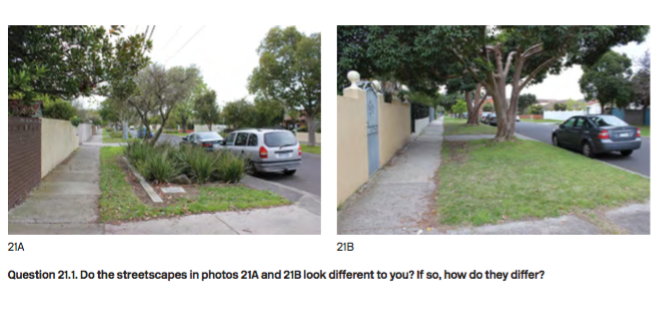

The study was conducted in four suburbs of Melbourne, Victoria, in which raingardens have been implemented: Richmond, Pascoe Vale, Chelsea and Mt Evelyn. Two streets in each suburb (one with a raingarden, one without) were located and photographed.

In a survey of residents from each street, 139 respondents gave their views on how they perceive, appreciate and value raingardens in their own and in the three other selected suburbs. To help with their understanding of a raingarden’s purpose, respondents were told that “raingardens are designed to capture and treat stormwater before it is discharged to the bay, reducing the amount of pollution that enters our waterways. It might also be possible to reuse the treated stormwater, to reduce the demand on mains drinking water and improve river and stream health.”

While it was obviously heartening to hear that streets with raingardens were preferred, Meredith said an interesting outcome, which will help future planning of raingardens, was that residents wanted raingardens not to have an adverse impact on parking availability, footpaths or other items of concern.

“A (particular) street without raingardens might afford more useful functions than one with raingardens, and this might influence preference for the raingardens. For example, raingardens lining a street might limit on-street parking, or their prickly vegetation spreading out over the footpath might interfere with walking your dog,” Meredith said.

“It is not what the raingardens actually look like but the restrictions they impose on how the street is used that can be important in shaping preference. If the raingardens, and the landscapes of which they are a part, are not liked, they are less likely to be cared for by the residents or wider community.”

Understanding the community’s preferences and catering to those can go a long way in helping urban water practitioners, planners and landscape architects “create urban landscapes that both function in harvesting, storing and treating stormwater and are also attractive to its residents.”

Rachelle Adamowicz, Regional Stormwater Coordinator (North East and Inner Metro) at Melbourne Water, has already seen some vital industry application from the research.

“Raingardens are an integral component of stormwater management and deliver multiple benefits to the community as well as protecting our waterways from the negative impacts of contaminated stormwater,” Rachelle said.

“Research like this is highly valuable because it reveals important factors in design features that can improve their attractiveness and the community’s appreciation of them. This will help ensure the longevity of the asset and the inclination to create similar systems.”

“I’ve seen studies that compare streetscapes with higher number of trees, nature, greenery with those that don’t, however not on raingardens specifically, so this is highly relevant to the work we do.”

Apart from establishing how attractive raingardens can make neighbours love their street, there is mounting evidence that economic benefits, in the obvious form of house value increases, may also improve their popularity.

In research for Valuation of economic, social and ecological costs and benefits (Project A1.2), Maksym Polyakov and colleagues looked at data on more than 4,400 house sales in Sydney between January 2008 and September 2014. The study found a strong relationship between median house value increases of more than $50,000 when a raingarden was located less than 50m away[1].

Findings such as this should encourage water authorities, local governments and urban planners to not only factor in raingardens to their future neighbourhood plans but also, importantly, to involve the community to ensure their long-term success.

[1] Polyakov, M., Iftekhar, S., Zhang, F., & Fogarty, J. (2015) The amenity value of water sensitive urban infrastructures: A case study on rain gardens. 59th Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural & Resource Economics Society, Rotorua, NZ, 10-13 February 2015.