Water leaders discuss how to mainstream the water sensitive city model

Chair of the Water Sensitive Cities Think Tank, Professor Tony Wong; Monash Sustainable Development Institute Director and the CRCWSC’s Chief Research Officer, Associate Professor Briony Rogers; and Director of the Rise Program and Senior Vice-Provost – Research at Monash University, Professor Rebekah Brown, have recently had an article published in One Earth. The piece is titled, ‘Transforming cities through water sensitive principles and practices’.

The paper discusses the water sensitive cities model, and particularly the lessons learnt since its principles were first proposed in 2009, the required actions for mainstreaming water sensitive practices, the next wave research agenda, and opportunities to catalyse actions in sectors beyond water. The crucial next steps outlined in the One Earth article will become the mission of the Water Sensitive Cities Institute, as the legacy vehicle of the CRCWSC when our term expires in June 2021.

Here is an extract from the article, reproduced here with permission:

We have come a long way in advancing water sensitive cities over the past decade. We have demonstrated applications of water sensitive cities principles at a range of scales and in policy reform. Responding to context is key, so guidance through a set of principles of practice is essential. Pockets of urban innovation focused on particular city challenges and opportunities exist nationally and internationally. Yet nowhere has achieved the cross-sectoral and cross-scale integration of infrastructure services needed for industry to ensure the long-term competitiveness, productivity and sustainability of cities.

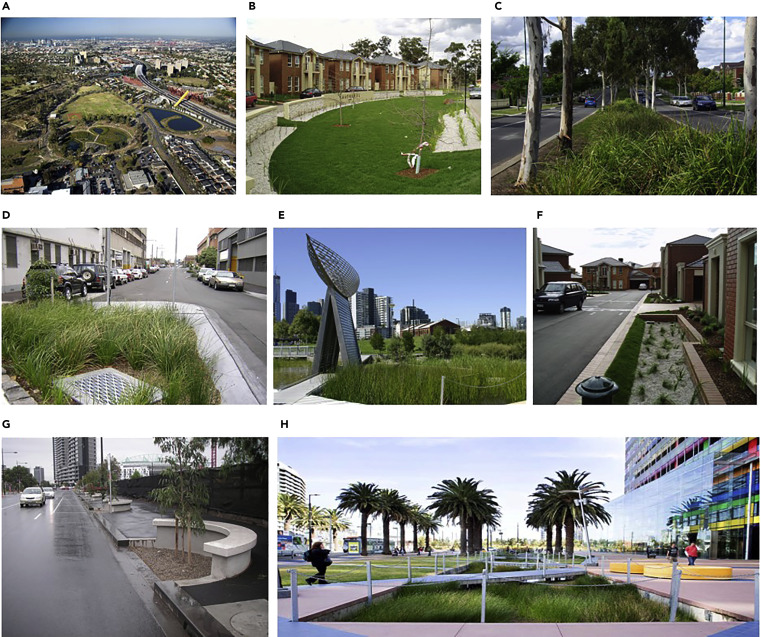

Water sensitive urban design (WSUD) is a place-based approach to integrating sustainable integrated water management and urban planning and design. Because it is place-based and context-specific, there are no standardised pre-conceived solutions, or solutions that can be readily transposed from one application to another. Only the principles of practice are common to all water sensitive cities transformation, which means cities have a limited ability to diffuse standardised solutions widely. As such, the types of obstacles to industry adoption overcome in the past decade largely related to a lack of place-based enablers, including:

- technical and design guidance and diagnostic tools for developing context-specific solutions, prioritising and balancing benefits, and devising suitable structural and non-structural interventions

- processes for collaborative design across multiple social-technical disciplines

- investment in collaboration, trials and experimentation of place-based water sensitive cities practices across multi-stakeholders

- policy promoting integrated urban water management with urban planning and design.

Some key obstacles remain, particularly in operationalising water sensitive city policies. This need is common across the world and must be addressed as we move to the mainstreaming and upscaling phase of water sensitive cities transformation. The three standout challenges are:

- developing a transparent and rigorous economic valuation basis for determining tangible and non-tangible economic benefits, and in monetising these benefits

- developing a business model that provides for whole-of-government and public-private sector co-investment of water sensitive projects

- integrating urban land use planning with water system planning in creating opportunities for water sensitive solutions through urban development processes.

As cities transition to become more water sensitive, the urgency of the complex challenges facing cities means we must not only develop and experiment with new hybrid solutions, we must rapidly bring them to scale. City stakeholders can already draw on significant actionable knowledge to rapidly progress towards their water sensitive vision. But upscaling and mainstreaming of water sensitive cities practices remains elusive—mainly impeded by institutional factors. Urban planning remains rule-bound to traditional practices that are based on highly fragmented and single dimension objectives, supported by outdated and narrow economic methods for assessing the benefit–cost of infrastructure investment. Overcoming these impediments and creating the enabling environment for transformations on a broader scale must become our collective mission.

At the heart of our lessons is embracing hybrid measures that can respond to local context. This is an emerging issue in many developed and developing cities as governments strive to augment their system capacity to accommodate increasing urbanisation, growing populations and climate resilience. Infill developments are prominent in urban densification and are often spatially piecewise. These features make them ideal opportunities to combine decentralised solutions with existing trunk infrastructure as integrated hybrid systems. By creating these hybrid solutions, we can ensure existing infrastructure is not stranded as we embrace emerging technologies and integrated system thinking. This approach ensures optimal economic returns from past and future infrastructure investments.

We have also learnt the water sensitive cities principles of practice are a useful orienting framework for interdisciplinary and integrated approaches to urban water management. They highlight the importance of expanding their use to other urban systems that shape our cities, for example energy, transport, waste, food production and the built environment. Coupling decentralised water and energy infrastructure with existing trunk infrastructure can increase system robustness and modularity. Architectural built form can be resilient and adaptive to floods. And we can develop infrastructure for waste-to-energy and the broader water–energy–waste systems. All of this infrastructure supports hybrid business models for whole-of-government and private-public sector co-investment and governance.

Experiences from water sensitive cities point to emerging directions for future research:

- participatory tools and evidence-informed policy, planning and design guidance to co-create hybrid solutions that reflect local values and improve human and ecological health

- leveraging social, policy, regulatory and economic enablers to create the authorising environment for accelerating mainstream uptake of hybrid systems

- new business and financing models, incentives and regulatory frameworks to unlock private investment in hybrid systems and encourage their delivery through appropriate sharing of costs, benefits and risks

- new metrics, technologies and decision support tools to optimise resources as part of a circular economy and increase infrastructure resilience through system integration

- smart infrastructure enabled through digital technologies.

This research agenda is diverse and ambitious. But we should also not ignore the existing knowledge that can already be leveraged, building on the practice changes that have been achieved through efforts to implement water sensitive cities. The CRCWSC’s Transition Dynamics Framework (TDF) provides the architecture of an action agenda that complements the research agenda proposed in this perspective.

We need champions at all scales of practice to inspire transformative action. We need platforms that bring people together in strong and influential communities of practice that have a common vision and evidence-based strategy for change. We need platforms that integrate interdisciplinary knowledge and make it accessible to the range of actors who must adopt new ways of doing things. We need scalable demonstrations of new solutions as they emerge. These solutions include technological innovations, but also social innovations such as urban design, collaboration processes, behaviour change methods and policy instruments. And finally, we need to emphasise evaluation and learning that help us understand change processes to drive system transformation from knowledge gained from individual project or practice interventions.

The water sensitive cities vision has progressed far in the past decade. In another 10 years, we may well see water sensitive practices becoming mainstream as city stakeholders collectively embrace the action agenda and research frontiers presented in this perspective. Through this, cities will develop transformative capacities to sustain their broader liveability, resilience and prosperity over the long term.

To learn more about the Water Sensitive Cities Institute, head here.