Alternative water supplies

Contact

Introduction

Alternative water supplies can be sourced from rainwater, stormwater, desalination, groundwater and recycled water. Recycled water refers to wastewater (sewage) that is treated and reused. Greywater is the cleaner portion of household wastewater (e.g. from wash basins, showers and washing machines).

Using alternative water supplies can help conserve high-quality drinking water by providing water for non-drinking needs like toilet flushing, clothes washing, sports field irrigation and industrial washdown. Alternative water schemes can be large (e.g. city scale) or decentralised water supplies (i.e. allotment or precinct scale). A water mass balance (analysis of inflows and outflows) can be used to quantify available water sources and demands.

Using water that would have ended up as waste or runoff, protects our environment from pollutants and retains moisture in the landscape. But, it is important to understand how this water will be used, to ensure it is treated and managed to meet regulatory standards and community preferences.

CRCWSC research can support cities and towns to use alternative water supplies to increase water supply security, avoid investment in upgrading existing, potentially unsustainable water infrastructure, and provide a local source of water for communities.

Research findings and reports

Our research on alternative water supplies has identified some interesting findings:

- A study to understand community acceptance of alternative water sources including stormwater harvesting, desalination and recycled water found the degree of connectedness, trust and shared values within a community were important for gaining support. (How social capital influences community support for alternative water sources)

- Using a water mass balance evaluation framework can help understand the urban water ‘metabolism' and how to best use alternative water sources to improve water security. (A metabolism perspective on alternative urban water servicing options using water mass balance)

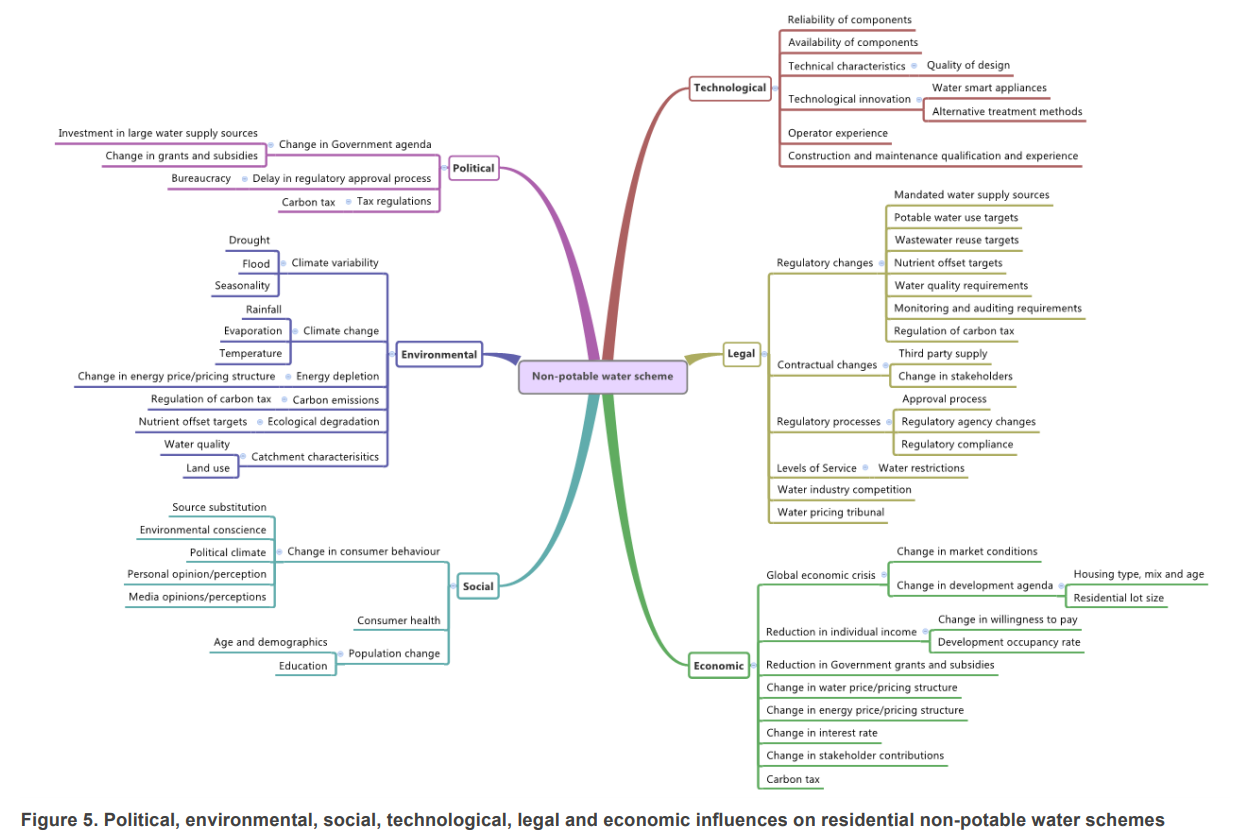

- The major supply and demand risks for residential alterative water schemes include political, environmental, social, technical, legal and economic influences. (Risks to the long-term viability of residential non-potable water schemes: a review).

- The different risk perceptions of stakeholders must be identified, acknowledged, and managed to gain acceptance of alternative water supplies. (Transition to a water-cycle city: sociodemographic influences on Australian urban water practitioners’ risk perceptions towards alternative water systems)

- Stormwater harvesting operating costs and supply reliability can be significantly impacted by storage volume and pump flow rate. (Optimization of Pumping Costs and Harvested Volume for a Stormwater Harvesting System)

You will find a range of research reports on alternative water supplies under the categories below.

Drainage and hydrology

- An interdisciplinary and catchment approach to enhancing urban flood resilience: a Melbourne case

- Modelling of green roof hydrological performance for urban drainage applications

- Source-control stormwater management for mitigating the impacts of urbanisation on baseflow: A review

Performance

- Factors that affect the dydraulic performance of raingardens: implications for design and maintenance

- Methodologies for pre-validation of biofilters and wetlands for stormwater treatment

- Verifying a stormwater biofiltration model

- Stormwater biofilters: a new validation modelling tool

Water quality and treatment

- Seasonal operation of dual-mode biofilters: The influence of plant species on stormwater and greywater treatment

- Quantifying sediment export from an urban development site: Heron Park

- Dual-mode stormwater-greywater biofilters: the impact of alternating water sources on treatment performance

- Biofilters and wetlands for stormwater treatment and harvesting

- Integrated multifunctional urban water systems: key findings from project C4.1

- Optimising nitrogen removal in existing stormwater biofilters: benefits and tradeoffs of a retrofitted saturated zone

- A preliminary model on E.coli removal in stormwater biofilters

- Validation framework for water-sensitive urban design treatment systems

- Health risk assessment of urban stormwater

Other

Research application

Our research on alternative water supplies has been applied to a range of projects:

- The Scenario Tool worked example: Highett Gasworks demonstrates how the tool was used to assess how various development options will impact urban heat and the water cycle in a hypothetical development at the Highett Gasworks.

- The Aquarevo greenfield residential development in Victoria demonstrates how homes can reduce drinking water use by up to 70% by harvesting rainwater for use in the laundry and bathroom.

- The Ocean Reef Marina in Perth explores 11 innovative ideas to be more water sensitive including treating stormwater and utilising alternative water for irrigation and boat washdown.

- The combination of subsoil drainage and treated wastewater is being used for irrigation of public open space as part of a development in Brabham, Perth.

- The Ideas for Liverpool Collaboration Area report illustrates how a revitalised recycled water hub could provide a resource factory for the Liverpool Collaboration Area.

Tools and guidelines

Several tools and guidelines, informed by our research, have been developed for use by practitioners:

- The Adoption guidelines for stormwater biofiltration systems provide guidance on using biofiltration systems as part of stormwater harvesting scheme.

- The INFFEWS tools, including the Value Tool and Benefit: Cost Analysis Tool, can be used to support investment decisions for alternative water supply.

- The blueprint2013: Stormwater Management in a Water Sensitive City outlines approaches to urban stormwater management as an alternative supply.

- The Scenario Tool is a planning-support tool that enables users to plan for and compare different development outcomes for urban infrastructure, water management and population demographics over time.

Infographics

Infographic 1

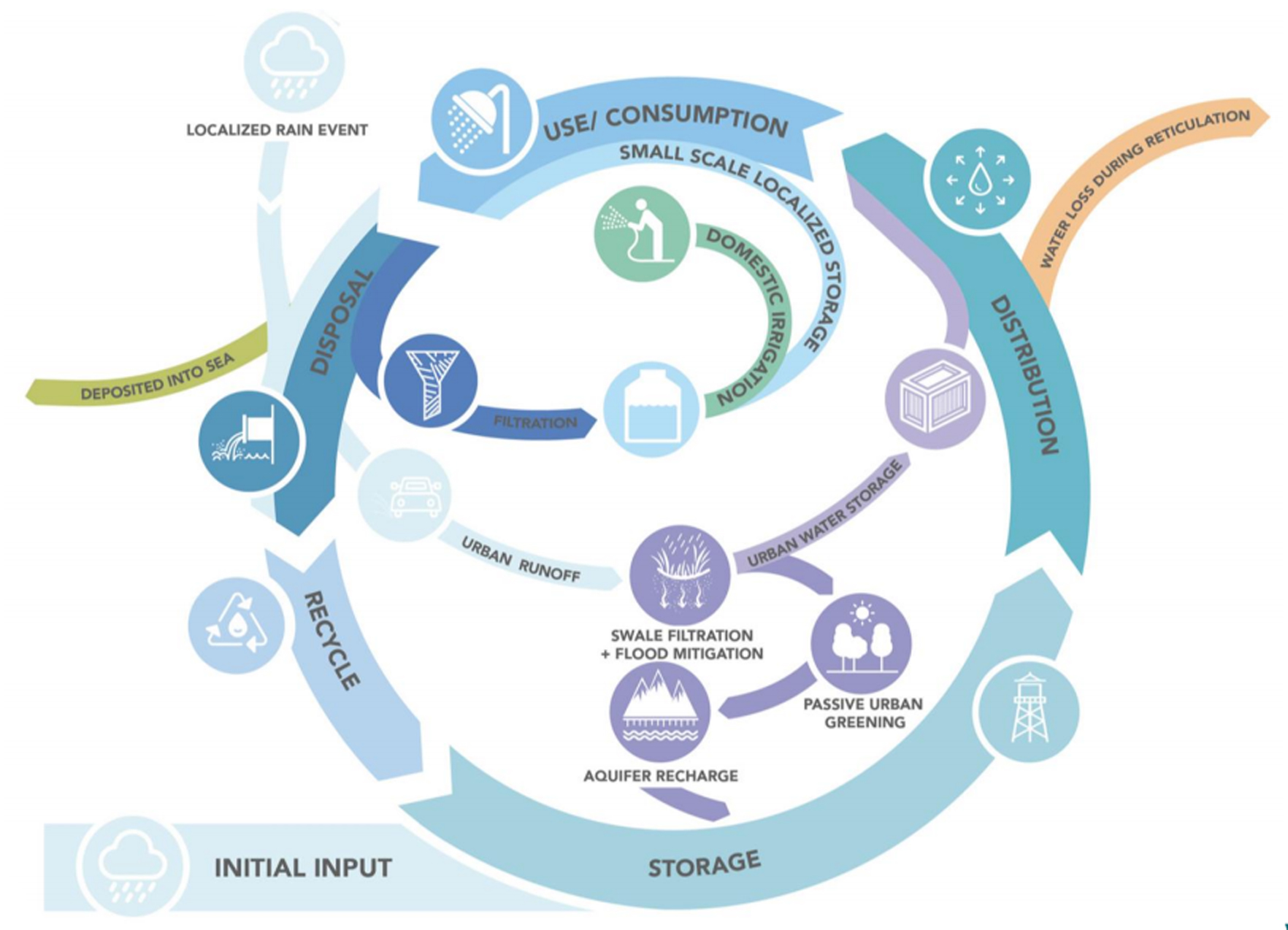

Circular economy (CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, 2019. Sydenham to Bankstown Urban Renewal Corridor: Workshop 3 on ground opportunities. Melbourne, Australia: CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, p. 28.)

Infographic 2

Water balance (CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, 2018. Ideas for Brabham. Melbourne, Australia: CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, p. 31.)

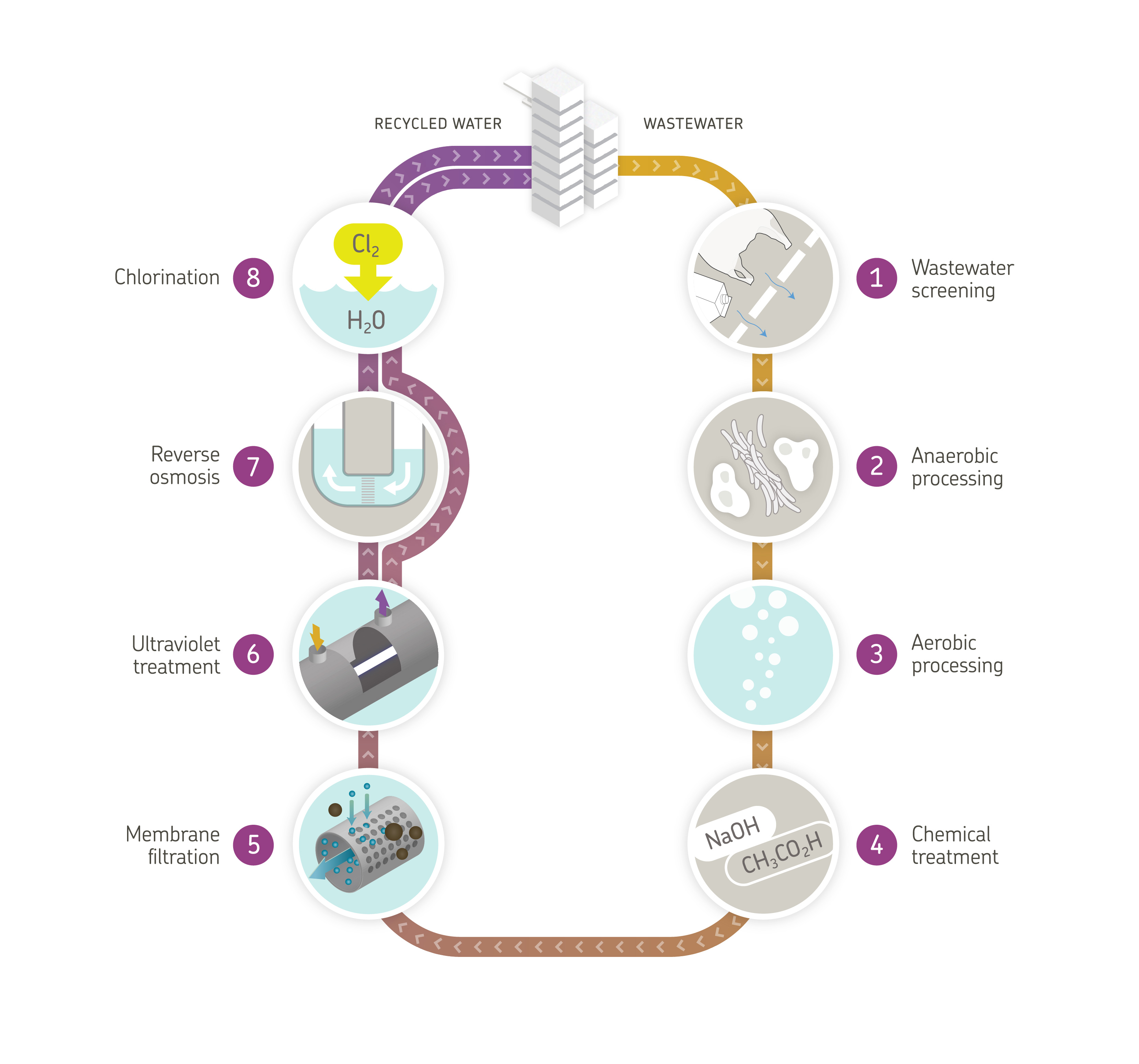

Infographic 3

Central Park recycled water scheme (CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, 2018. Central Park recycled water scheme. Melbourne, Australia: CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, p. 1.)

Infographic 4

Comparison of available roof water to residential water demand (CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, 2018. Warrnambool roof water harvesting project. Melbourne, Australia: CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, p. 5.)

Infographic 5

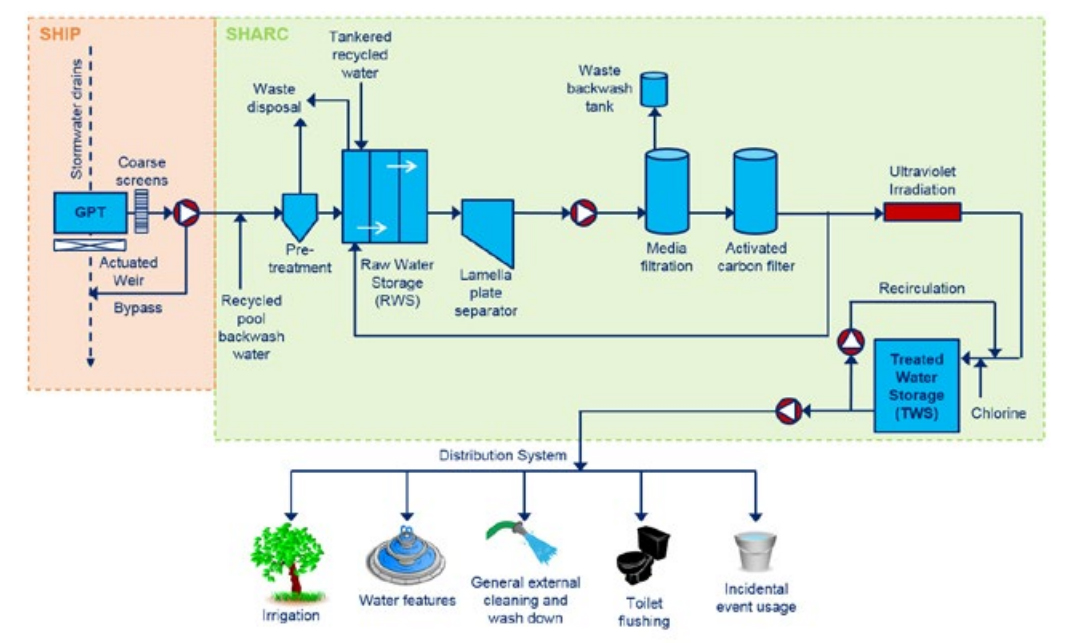

South Bank Rain Bank treatment process (CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, 2018. South Bank Rain Bank. Melbourne, Australia: CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, p. 22.)

Infographic 6

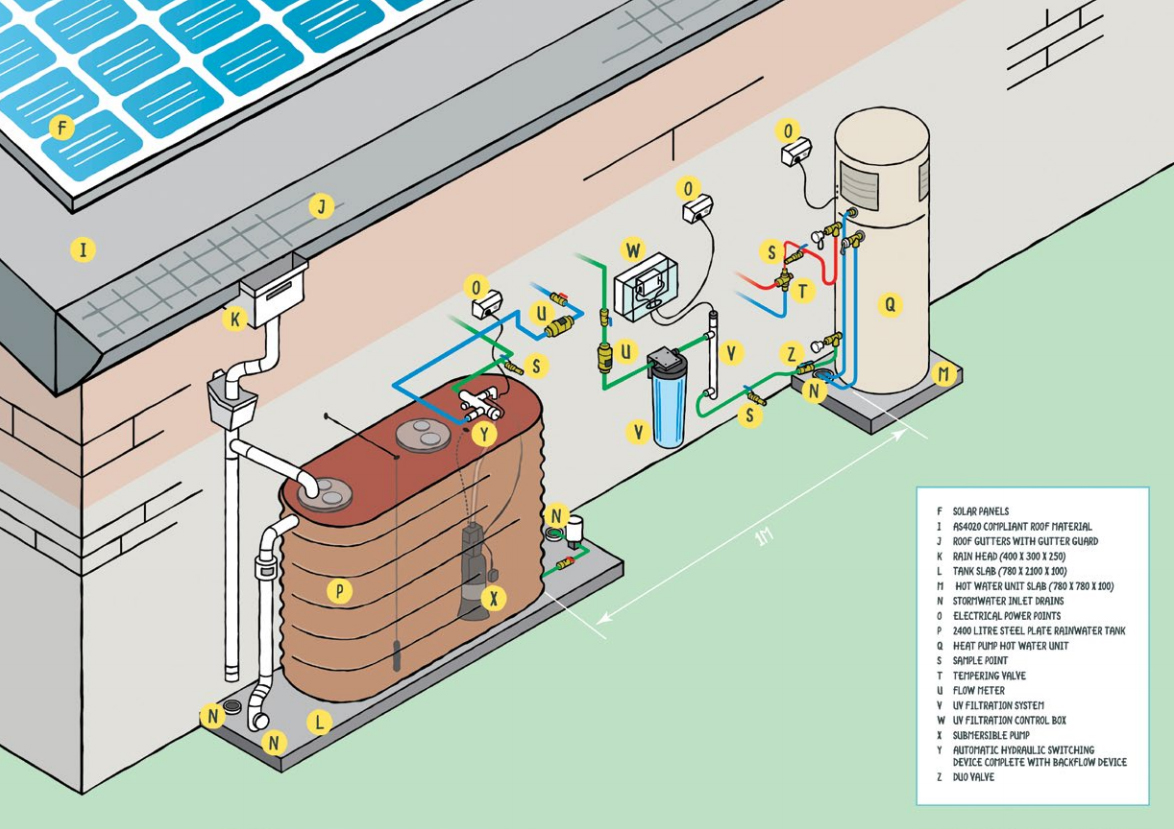

Components of the roof water supply to hot water system (CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, 2017. Aquarevo: a smart model for residential water management. Melbourne, Australia: CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, p. 19.)

Infographic 7

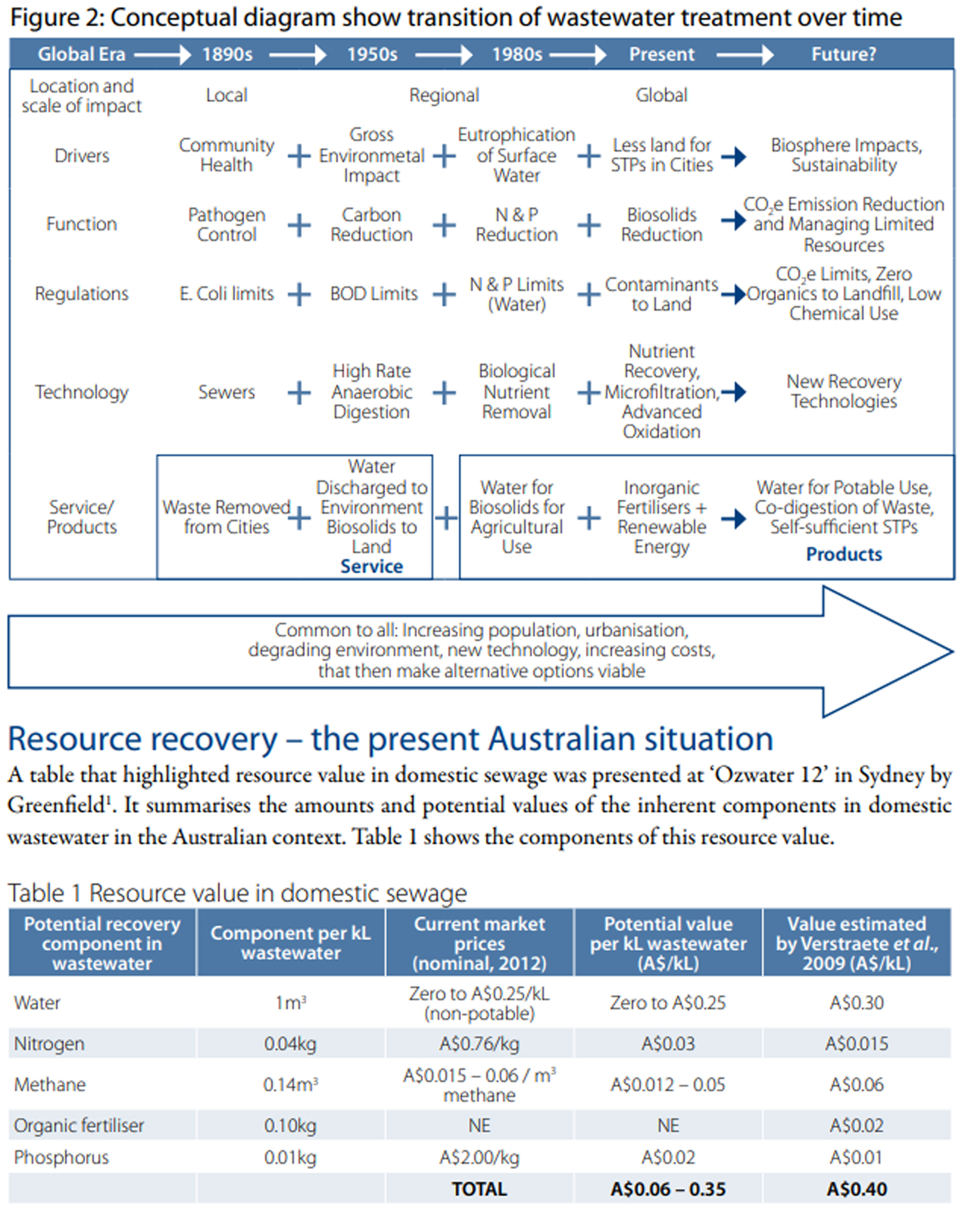

Conceptual diagram showing transition of wastewater treatment over time (Burgess et al., 2015. Wastewater – an untapped resource? Report of a study by the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering, p. 11.)

Infographic 8

Political, environmental, social, technological, legal and economic influences on residential non-potable water schemes (West et al., 2015. Risks to the long-term viability of residential non-potable water schemes: a review. Melbourne, Australia: CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, p. 37.)

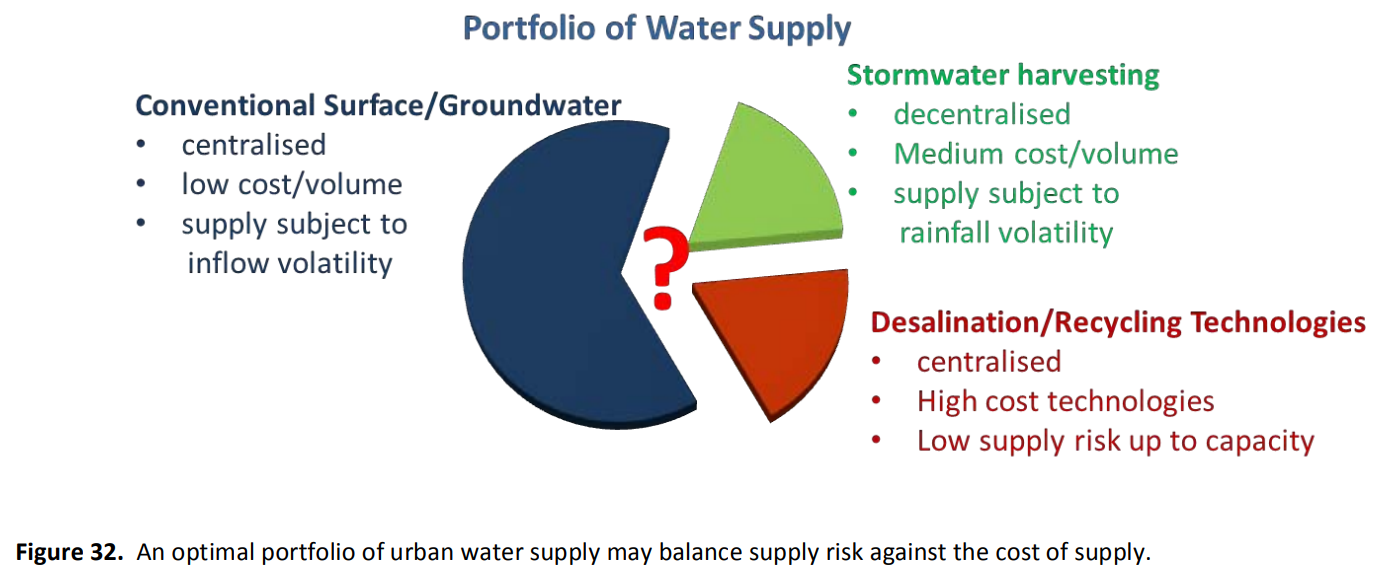

Infographic 9

An optimal portfolio of urban water supply may balance supply risk against the cost of supply (Wong et al., 2013. blueprint2013 – stormwater management in a water sensitive city. Melbourne, Australia: CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, p. 72.)

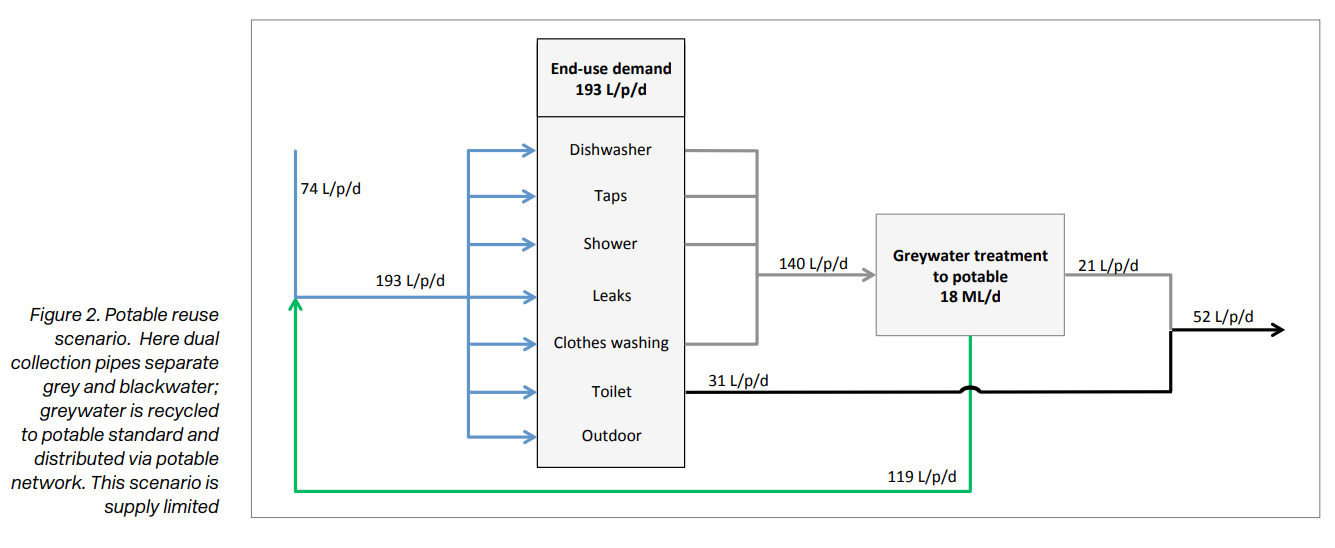

Infographic 10

Potable reuse scenario (CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, 2015. Ideas for Fishermans Bend. Melbourne, Australia: CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, p. 39.)

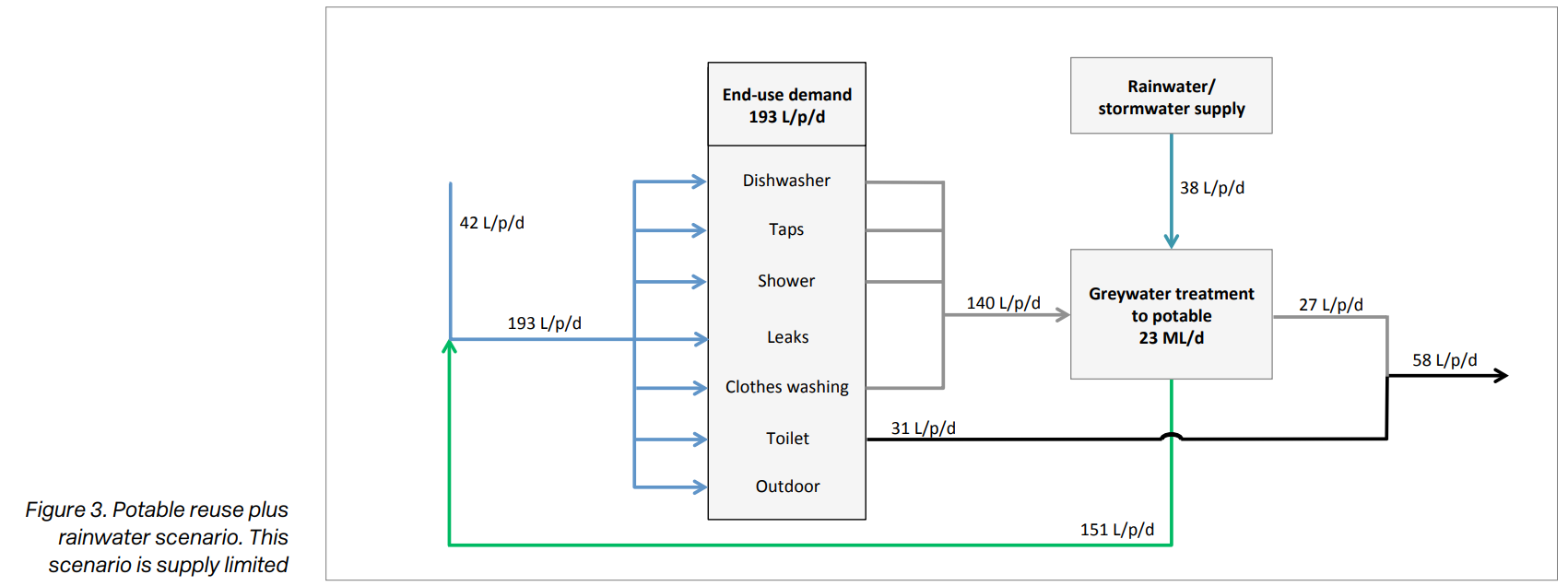

Infographic 11

Potable reuse plus rainwater scenario (CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, 2015. Ideas for Fishermans Bend. Melbourne, Australia: CRC for Water Sensitive Cities, p. 39.)